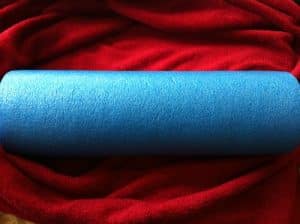

If you’re new to Feldenkrais, you might not be familiar with the idea of using “rollers” in the context of Feldenkrais sessions.

In gym culture and physical therapy, rollers are often used for self-massage, stretching, or so-called “myofascial release.” But this has little to do with how Moshe Feldenkrais used them.

In Feldenkrais and other somatic approaches, rollers are used to support the body gently, precisely, so it can rest more fully, move more easily, and learn without strain.

Moshe began using rollers back in the 1950s—but not for massage. They weren’t even made of foam at first. He used wood, cardboard tubes, and other soft materials in various sizes to support different parts of the body.

Some went under the ankles or knees while lying on the table. Others were used under the spine, or the neck. The goal was never to press or release tissue—it was to support the person just enough so their system could organize itself more efficiently.

Moshe used rollers to place a person’s body in a position that echoed upright standing. He believed that if the nervous system could experience new movement patterns while lying down—but still organized like standing—those patterns would be more likely to carry over into daily life.

He once described it like this:

“When you put a person on the bed [Feldenkrais table] you must support all the gaps… with rollers, sponges, little pieces of rubber… What for? To bring the lying body into a state where the reaction from the table would be uniformly annihilating the weight.”

In the late 1980s, physical therapist and Feldenkrais student Sean Gallagher began using foam rollers for self-massage. Accoring to the website Physical Culture Study, he introduced the idea to Broadway choreographer Jerome Robbins, whose dancers were performing night after night. The cast experimented with rollers backstage—and the results were so positive that they quickly became a staple for dancers on Broadway.

Then, in the 1990s, physical therapist Mike Clark helped rebrand foam rolling as “self-myofascial release.” His training manuals and fitness programs helped spread the technique across gyms, clinics, and athletic performance centers. By the 2000s, foam rolling was everywhere.

That’s why I couldn’t help but laugh earlier today when I read a New York Times article called “The Best Foam Rollers.”

It opened with:

“Foam rolling... is extolled by physical therapists, massage therapists, and personal trainers alike for improving flexibility and reducing stiffness (and even pain).”

Plenty of praise. But not a single mention of where foam rollers actually came from—or how they were originally used by Feldenkrais and other somatic pioneers.

There is nothing wrong with using rollers however you want to. If they work for you, that’s great! I simply want to point out that their origin—at least in the world of movement education—had nothing to do with grinding out tension or “breaking up” fascia.

Moshe Feldenkrais used rollers to reduce effort, not create it.

To quiet the system, not challenge it.

To make learning possible by making comfort available.

That’s the difference.

Not pressure. Not pain. Not effort.

But comfort that allows for change.

So next time you see someone grimacing and grinding on a roller at the gym—just know:

It didn’t start that way. And his rollers were never about pain.

They were about possibility.

Peace!